The National Parks System is one of our country’s best ideas for so many reasons. It would be nearly impossible to list all the benefits we collectively gain from these protected and public lands. One of the clearest, however, is the living laboratory of national parks and their ecology — the way in which they provide a window into how nature takes course outside of major human impacts. Today, we discovered that Glacier Bay National Park may be one of the best examples of this.

We began our morning at the face of Johns Hopkins Glacier, one of the many tidewater glaciers snaking from the upper elevations of the Fairweather Mountain range down to the warm(er) ocean waters of Glacier Bay. Like all other glaciers here, Johns Hopkins is rapidly receding, leaving bare earth behind ready to be colonized by plants, animals, and fungi. Over the past 200 years, this has happened across the area of the park, leaving behind over 60 miles of new earth and water. Blank slate for life to takes its course.

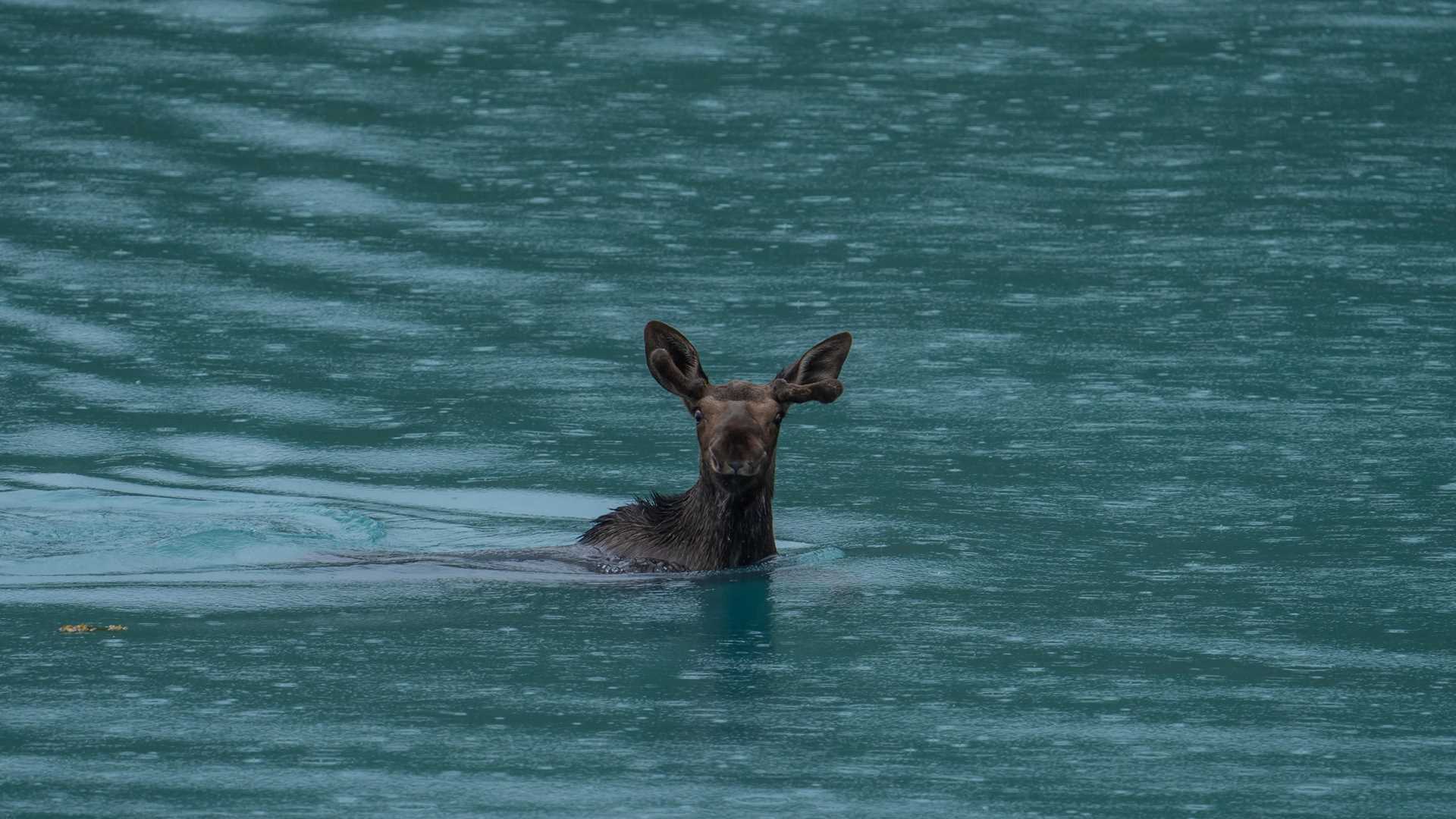

Throughout our day of cruising, we were lucky enough to see an entire range of the life that has followed in the wake of the ice. Among the thickets of alders and hemlocks, our naturalist team and deck team spotted a lone bear feeding along the coastline. Soon, three more appeared followed by a moose that began to swim in an apparent escape from the hungry predators. A stunning encounter that set the tone for a day full of sightings. Rafts of sea otters floating gently in the glacier blue waters. Killer whales slowly swimming along the coastline. Mountain goats scrambling up sheer granite cliff faces, seemingly vertical. Thousands of sea birds nesting in safety on isolated islands. And 6 more coastal brown bears foraging for food as they wait for the salmon run to begin.

The amount of life we were lucky to find here today shows just how resilient life is and how quickly it can flourish from nothing when given the opportunity, thanks to the protections of our National Parks.