La Gomera is one of less frequently visited islands in the Canarias, having been deliberately protected from the more ruthless commercial developments associated with the monoculture of mass tourism prevalent elsewhere on the archipelago. Interestingly our guide on the day tour of the island, although he had been working as a guide for over quarter of a century, had never before worked with an American group. The island has a population of just over 20,000 and is the second smallest island in the archipelago. Of volcanic origin, it is no longer considered active and its geomorphological interest derives from a long period of erosion since that active phase, with prominently exposed volcanic plugs. Some 14 miles in diameter, the island rises to nearly 5,000 feet and our bus driver earned every euro of his gratuity negotiating hairpin bends and steep gradients throughout the day.

The upper reaches of the island have been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site for its native laurisilva, an extensive area of laurel rain forest that covers the upper slopes of the barrancos, deep ravines cut by Atlantic rainfall, of which there is some 50 inches per annum at these high altitudes. Having made our way up to the Garanjoy National Park, we lunched at a local tavern on local fare, including almogrote (a cheese spread), fresh goat cheese, a hearty potage and local fish, washed down with the distinctive local red wine. After lunch we were treated to a demonstration of silbo Gomero, a traditional whistling “language” that enabled villagers to communicate over a range of some two miles in this rugged landscape.

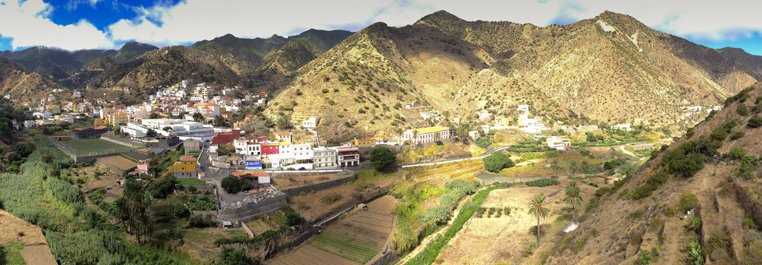

Tourism has displaced agriculture as the prime economic mover on the island and it was sad to see so many fields abandoned. The evidence of centuries of terracing up the steep hillsides spoke eloquently of former productivity and the backbreaking labor that accompanied it. Many of the early terraces, it is believed, were dug out by the Guanche peoples who were living on the island when the Spanish arrived, for the Canary Islands are the only archipelago in our tour of Macaronesia that had pre-colonial inhabitants. Linguistic and place-name evidence together with recent DNA studies enable the Guanche to be identified with certainty as a Berber people from neighboring North Africa. Interestingly, the combined effects of centuries of Reconquista on Spanish history and culture together with a strong desire to exert their European credentials in terms of EU membership made investigations into the archaeology of the Canary Islands a surprisingly controversial field until quite recent times. As far as physical geography is concerned, we were closer to the African continent at La Gomera that at any other point of our voyage.

La Gomera was the last port of call of Christopher Columbus before he embarked on his epoch-making voyage of discovery in 1492. The links with the New World are evident in the local population, with extensive family connection with Cuba and Venezuela in particular, and with local recipes, including gofio, for sprinkling on the soup, an early example of the use of maize, the native Americas’ greatest gift to the world, in the Old World. The lesson here, as so often in Macaronesia, is that isolation is more apparent than real.